For almost as long as I’ve been in sustainability circles, there’s been an always-old joke about the seeming intractability of the climate problem. Sparing you the long-winded details, the punchline has God break down in tears at the knowledge they won’t live long enough (God, that is!) to see the climate crisis solved. (In the right hands, that little story brings down the house. In mine - groans and crickets.)

Funny or not, it captures a truth about the climate movement. For almost as long as we have understood and spoken of climate change, we’ve been beset by pessimism, despair, and gloom. It always looks so insurmountable, and our progress has been slower than anyone counted on. Of course we despair.

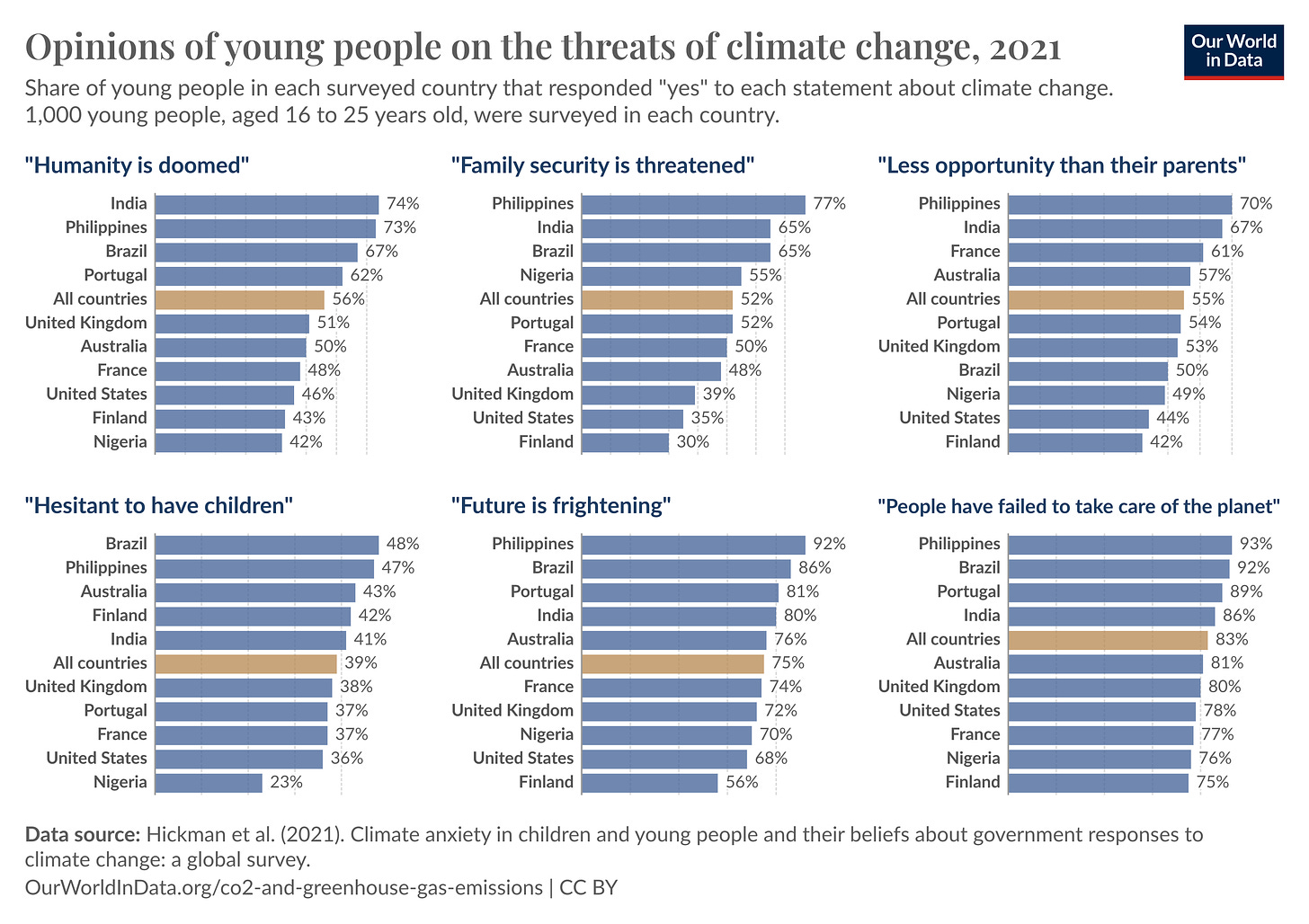

To illustrate: In 2021, fifty-six percent of young people around the world felt that “humanity is doomed”. Another seventy-five percent reported that the “future is frightening”, and 83% agreed that “people have failed to take care of the planet.” Look at this summary of those findings from the very excellent website Our World in Data.

It was also in 2021, by coincidence, that I attended a lecture on biodiversity in which the lecturer, a Canadian university professor, concluded his otherwise scientific presentation with advice on mental health. An overwhelming proportion of his students, he explained, were struggling with depression and anxiety as a direct result of their study of environmental issues. He couldn’t responsibly present his perspective on biodiversity without also giving mental health advice.

This is where we find ourselves.

That was also the context when Adventure Canada (where I am now the Director of Sustainability & Regenerative Travel) asked me to prepare a hopeful lecture on climate change to deliver aboard their Arctic expeditions. Although no climate specialist, I’ve been in and around the sustainability field for over thirty years. I have gradually migrated to a perspective on sustainability that sees “environmentalism” through a lens of human well-being. That is the lens I bring to this challenge, and that is the lens for all of my current work and for this short series of articles: A Case for Climate Hope and Optimism.

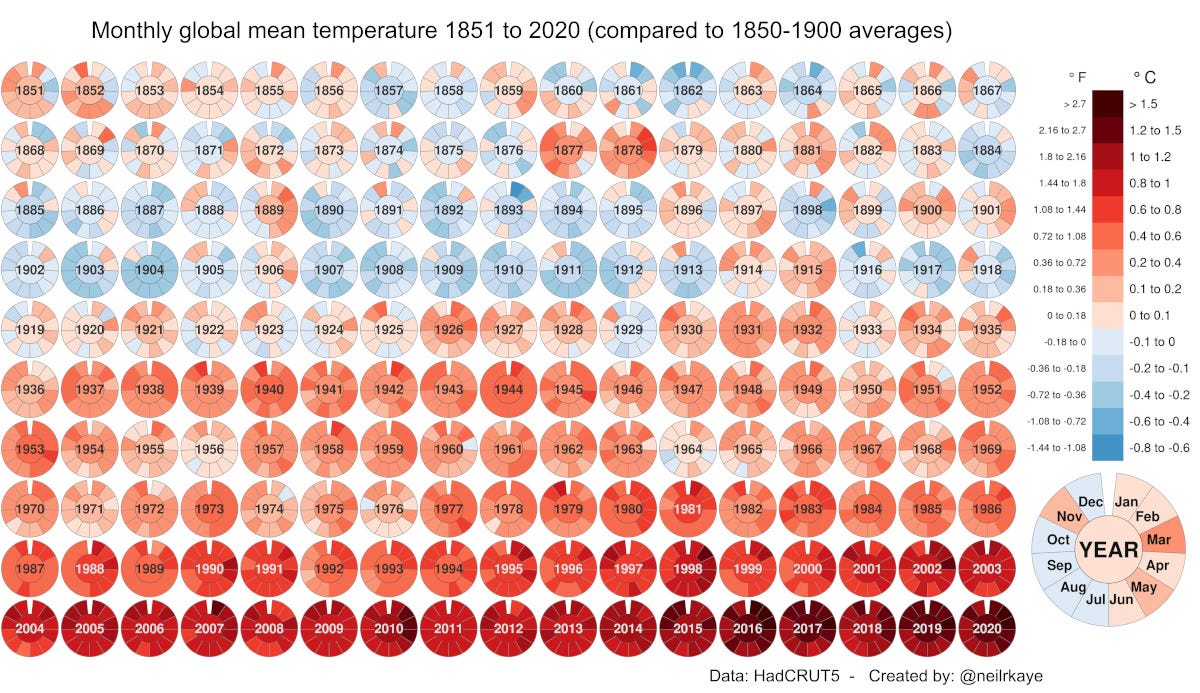

So we don’t get pollyanish about all this hope and optimism stuff, let’s start with this hard reality: the climate crisis is very real, very present, and very urgent. Just look at this excellent graphic from the Visual Capitalist to understand the warming trend:

Our warming climate is causing coral bleaching, rising sea level, polar and glacial ice melting, climate refugees, loss of food productivity, and intolerable urban heat extremes. It is real, it is present, and it is still worsening. The planet itself is not threatened by this – the planet has seen worse and will see worse again – but the planet as we know and love it is very much in jeopardy. There is much work to be done, and there is a role for each of us.

Let’s also agree on this before we get started: hope and optimism are only useful to us if they motivate action, and not complacency. I like to put it this way: Evidence for hope. Hope for action. Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data (a superlative resource that I lean on very heavily and encourage you to explore) puts it like this: “Optimism is the only thing that works — but only if we don’t assume that progress is inevitable.” In other words, optimism is essential but it’s not enough. Optimism-fuelled action is the endgame. (Optimism: the ultimate renewable resource?)

An Argument in Three Parts

Each of the next three articles in this series will tackle one of the three principal arguments I make for the Case for Climate Hope & Optimism.

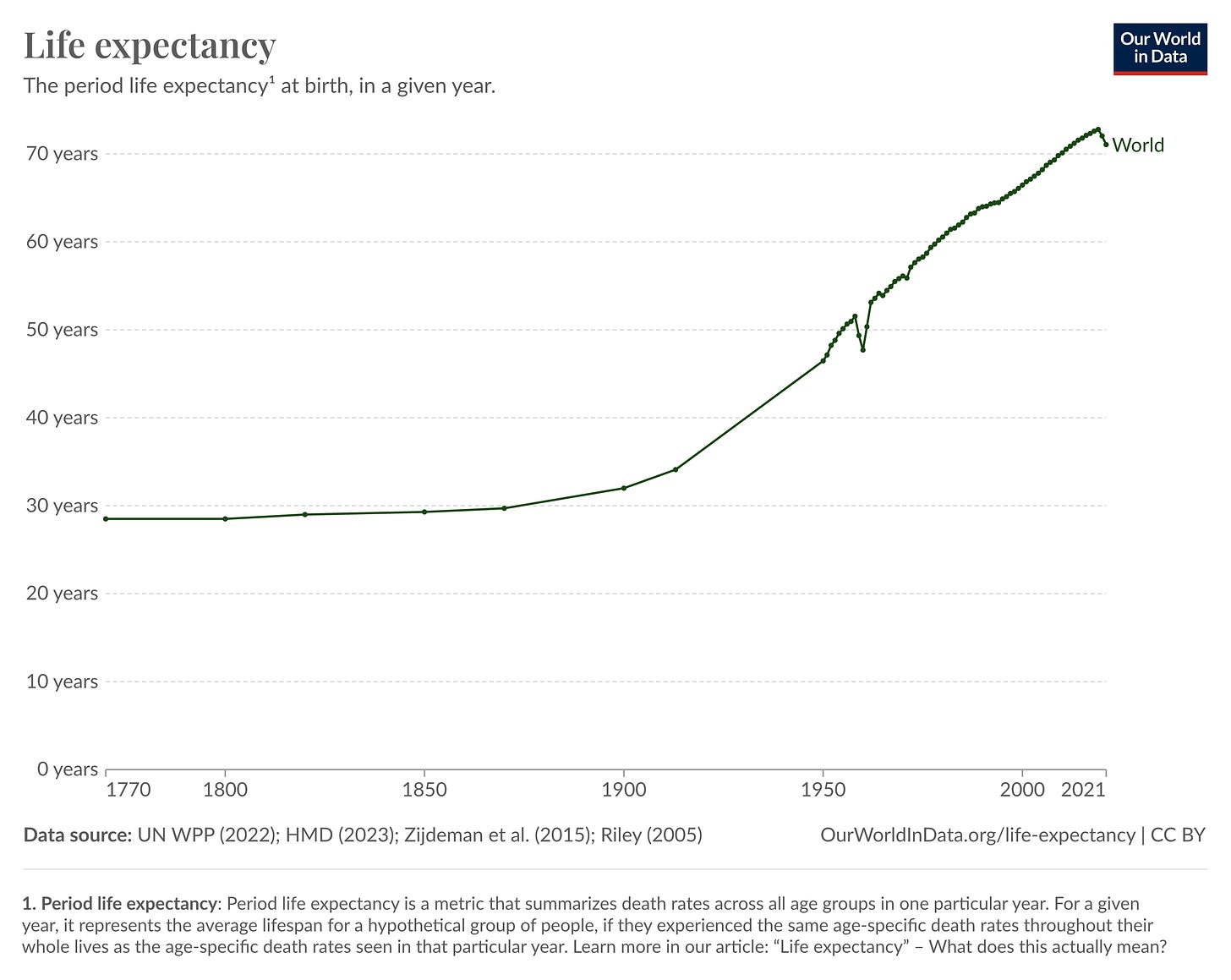

The first argument is that we – as a species – have solved big problems before and this should give us some confidence that we might solve the climate crisis as well. In fact, counter-intuitively, climate change is itself the collateral damage of humans solving the biggest problems that faced them in the 19th century: economic struggle, disease, widespread poverty, and tragically short and desperate lives. The average human lifespan before the industrial revolution was less than thirty years of age. Today, it is more than seventy.

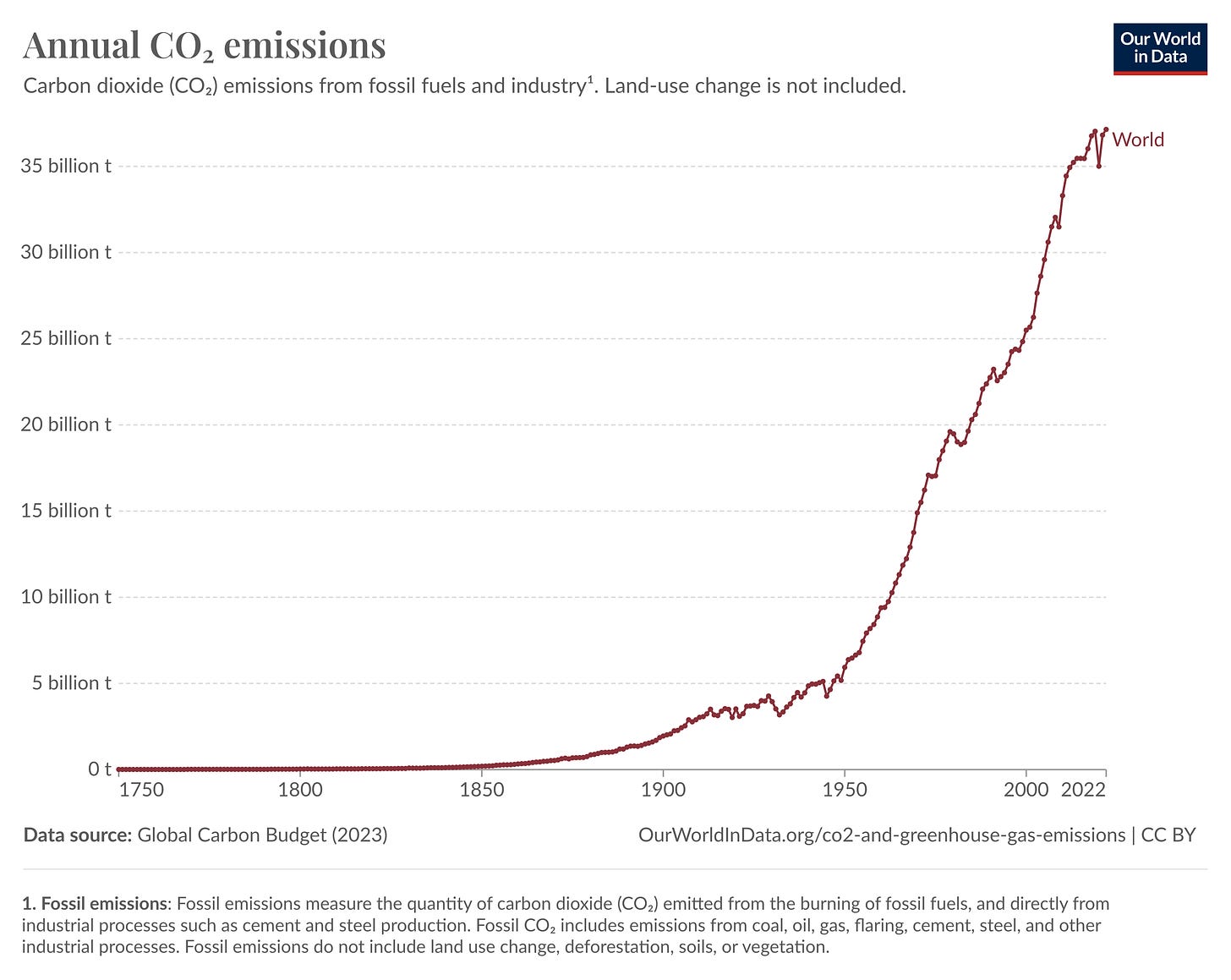

The industrial revolution - think the 19th century with a key turning point around 1850 - is when we began systematically energizing our world with fossil fuels. It is the combustion of fossil fuels and the greenhouse gases that result that set us on our present path of global warming. Look at this graph illustrating emissions of carbon dioxide over time.

And this one, showing life expectancy.

This is no quinky-dink. This is direction causation. Fossils fuels have given us the world as we know it today and - for all its terrible inadequacies - it is a much better world today for virtually all humans than it was before the advent of fossil fuels.

Of course, climate change is hardly the only adverse effect of the industrial age. An inventory of environmental harm would be long and diverse, and it would be a terrible lie to say we’ve taken all those challenges seriously. Nevertheless, there are examples of threats that we humans have deemed so serious that we’ve turned swords to ploughshares, put our heads together, found solutions, and cooperatively deployed them. For example:

· Acid rain, virtually eliminated.

· Ozone-depleting substances, virtually eliminated.

· Lead pollution, virtually eliminated.

There’s an upper-case caveat emptor here, of course: Fixing none of these environmental challenges involved the kind of fundamental re-invention of the world that the climate crisis will require. Our modern civilization is – quite literally – built on fossil fuels. To mitigate climate change, we will re-invent everything. On the other hand, these examples do prove that we humans can, and sometimes do, get together and do the right thing. Sometimes, it’s the challenges that bring out the best in us.

The second argument is that we already have made and are making much greater progress to combat climate change than the popular press would have you believe.

Here is what the evidence on climate tells us about our progress:

· Global emissions of CO2e have already begun to plateau and are in decline in the G7 and EU nations.

· Renewable energy technologies are now the least expensive of all options in almost all parts of the world.

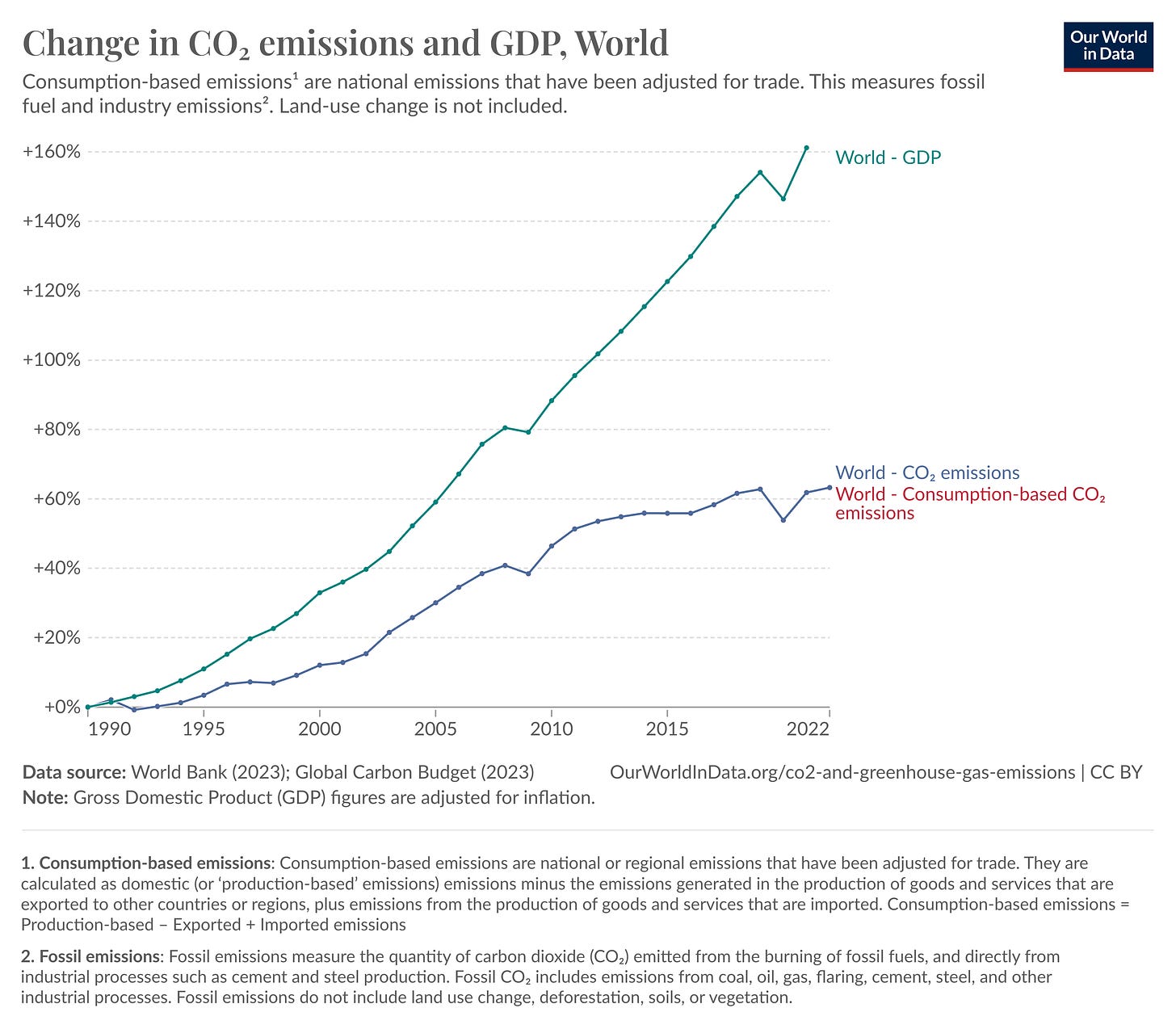

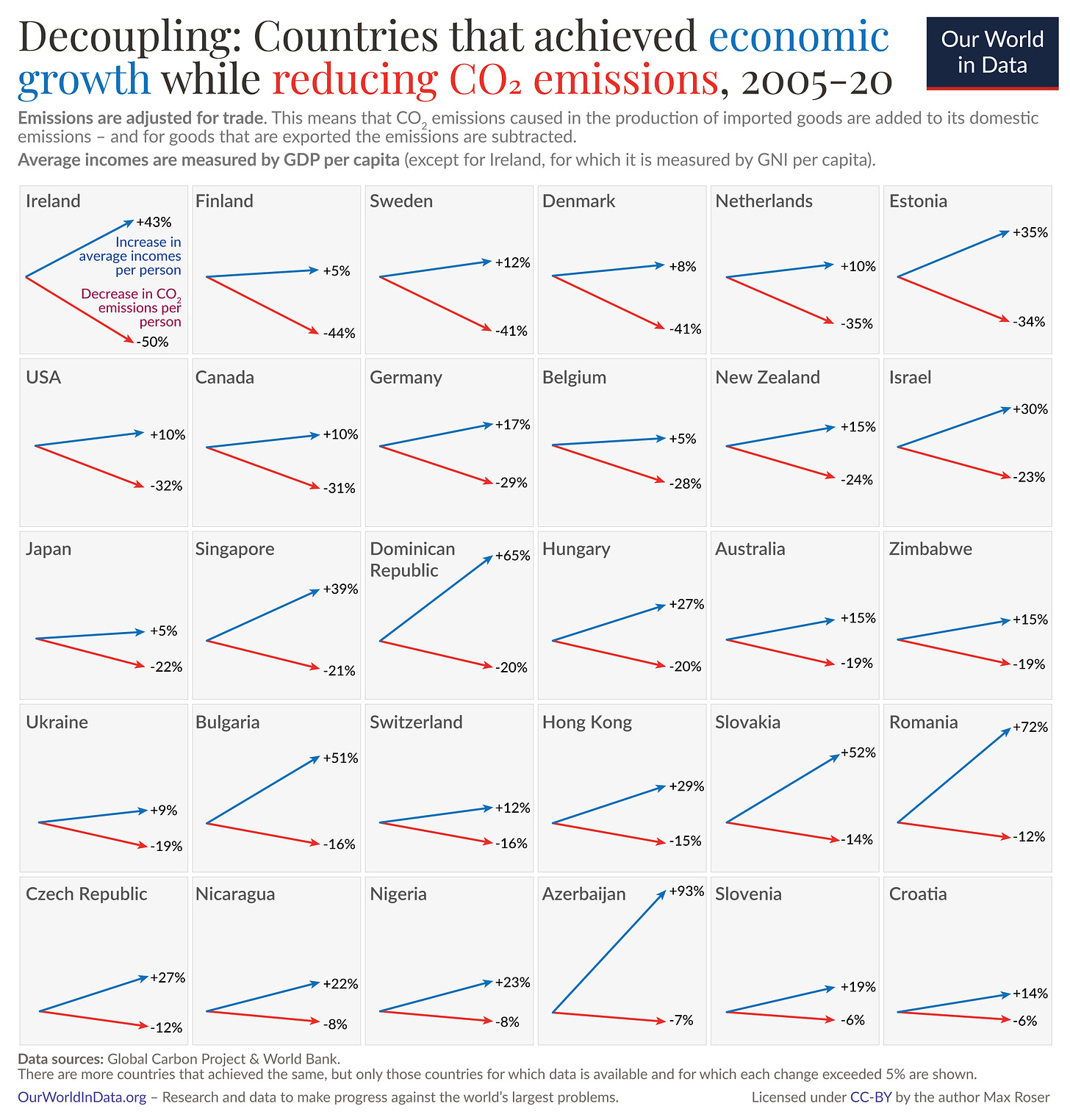

· Perhaps most significantly, economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions are being decoupled, meaning it will be possible to deliver economic prosperity (especially in the global south where it is most desperately needed) without a proportionate increase in greenhouse gas emissions. This is illustrated in the two images below.

To again quote Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data, when it comes to climate change “pessimists look at the news, while optimists look at the data.”

The third argument is simply that - as we all know - optimism is necessary for us to rise to the challenges of our lives. If we can find legitimate reasons for optimism, we should.

This least empirical of the three arguments is the most intuitive to most people. When I bring it up in a presentation, I enlist the audience’s help to make the qualitative more quantitative: “Raise your hands,” I’ll say, “if you’ve ever faced a challenge in your life that at first felt insurmountable.” Almost every hand will go up. “Keep your hands up, please,” (Simon says) “and only lower them if it was pessimism that got you through.” Virtually every raised hand stays up. The collective wisdom of every audience I’ve addressed on this subject is that optimism is necessary for us to rise to the challenges of our lives. Again: If we can find a reason for optimism, we should latch on to it.

Helen Keller said “Optimism is the faith that leads to achievement. Nothing can be done without hope and confidence.”

Jack Layton said “My friends, love is better than anger. Hope is better than fear. Optimism is better than despair. So let us be loving, hopeful and optimistic. And we'll change the world.”

Noam Chomsky said “Optimism is a strategy for making a better future. Because unless you believe that the future can be better, you are unlikely to step up and take responsibility for making it so.”

Wayne Dyer said “If you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.”

And, of course, Yoda: “Try not. Do .. or do not. There is no try.”

In the next three articles in this series, I’ll elaborate on each of these arguments. I hope to engage you about whether or not there are evidence-based reasons for optimism on climate. This is important, I think, for several reasons.

· Because despair and pessimism are active obstacles to the climate action we urgently need. As climate researcher Michael Mann says “doomism today arguably poses a greater threat to climate action than outright denial”.

· Because for the sake of the mental health of our friends, families, and communities – and especially our kids and youth – we must address the modern mental health plagues of “eco-anxiety” and “eco-despair”. We need to give and be given evidence to abandon this despair.

· Because in this challenge there is the possibility of a beautiful – almost miraculous - vision for humanity across geographies and generations. Like all organisms, we can outgrow and over-exploit our environments. Stretching our environment to the breaking point is the most natural thing in the world for a dominant species: arctic wolves and caribou, African lions and wildebeest, lynx and snowshoe hare. The predator-prey boom-bust cycle. What we are trying to do – a thing that has never been attempted let alone accomplished by any other species (by any other species!) in the history of the world – is to think our way out of that boom-bust cycle. Think of the achievement already represented in the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, the United Nations body that addresses climate change): a body representing virtually every human on the planet that brings together our best and brightest in an optimistic effort to do a thing so unnatural, so beautiful, and so exciting that it’s never been done before. In the universe. Ever.

We stand on the shoulders of those imperfect beings that came before us, just as our imperfect kids and grandkids will stand on ours. We are united in this beautiful multi-generational project. It’s time for us to see the beauty in it, to double-down on reasoned optimism, and to move forward in love and ambition. .

Love it Scott. Will be including parts of this in my sustainable design lessons.

Alright Scott! Good start. Looking forward to more.